Each day hundreds of millions of gallons of water pour in and out of the Bay with the rising and falling of the tides. All this moving water creates currents that push around obstacles and islands and can push an unsuspecting boater into problems, or leave them stranded far from home. A critical part of Boating safely on the Bay is understanding Tides & Currents.

Tides

TIDE is the HEIGHT of the surface of the water. This is affected by the moon’s and sun’s gravity pulling on the oceans.

Daily Tidal Cycle

In California, the tide rises and falls twice per day as the earth rotates. One high-tide is usually higher than the other. In San Francisco Bay, the tide can change by as much as 8 feet in the space of six hours

<< Picture of the dock or breakwater at high tide vs low tide >>

Monthly Tidal Cycle

High tide is not the same each day. As the moon orbits the earth, it pull the tide cycle with it. The tidal cycle moves forward about 50minutes every day. So if it’s high tide at noon on Tuesday, it’ll probably be high tide just before 1pm on Wednesday, and maybe 1:45 on Thursday.

The height of the tide changes through the month too. Tides are largest, and currents are strongest on the new moon and full moons when the sun and moon are in alignment.

Annual Tidal Cycle

The tides are also influenced by the earth’s orbit around the sun, and you’ll see particularly extreme tides around the weeks of the solstice. These tides are known as ‘king’ tides, and can cause flooding along the shoreline.

Forecasting Tides

The tides are predictable and you can find them in a tide book, various places online, and in marine apps such as Navionics. At the club, you’ll be able to find a copy of the tidebook by the log book at the signout desk.

The tide rises and falls twice per day. This is an example:

https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/noaatidepredictions.html?id=9414792

Things to note:

- The tide level rises and falls in smooth curves.

- Two High Tides per day. One is higher than the other.

- Two Low Tides per day. One lower than the other.

So, why are the tides important?

The tide often hides rocks, or makes obstacles appear where they weren’t before. Of note, there is a Little Alcatraz – a large rock off the north end of Alcatraz that is submerged at high tide, and frequently catches unaware boaters by surprise.

Low tides are fun for doing low tide exploration. Pick a low tide to look at starfish and mussels clinging to sea walls. Or enjoy a high tide to see above piers and to get a different perspective on the water.

At low tide, the dock apron can be very steep. Watch your footing and remember to tie your boat to a cleat if you leave it unattended on the slope.

But the main reason to be aware of tides, is because tides create current!

Currents

As the tide rises out in the ocean, water ‘floods’ into San Francisco Bay and flows up to all the other bays and tidal channels upstream. As the tide falls, all that water ‘ebbs’ back out to the ocean. This movement of water is called current.

Current is the FLOW of water in and out of the bay. Tides are vertical, currents are horizontal. As sea-level drops or rises with the tide, water flows in and out of the bay.

At times the water may be flowing out to sea at more than 4 knots (1 knot = 1 nautical mile per hour which is about 1.2mph) – That is likely faster than you can probably row or paddle!

- Flood – Water flowing into the bay. (F = Filling)

- Ebb – Water flowing out of the bay. (E = Emptying)

- Slack – The time between an ebb and flood when the water is not moving much.

Like the tides, currents can be forecast with a fair amount of accuracy. You can also find currents in the tidebook, or online sources listed on our weather page.

The current section of the tidebook will help you identify times of peak flow (speed) and slack water between.

In a given day, it’ll flood twice, ebb twice and there’ll be four periods of “slack” between them.

NOTE: High/Low Tide does not mean NOT Slack Current

You should imagine the tide creating a very long, slow wave that spills into and throughout the bay. The wave has its own momentum and it takes time for the rising waters to reach far up into the north bays. It’s important to realize that water can still be flowing into the bay even after high tide has been passed. It can even be flooding strongly at the Golden Gate bridge, even though the tide is going down.

Variance Due to Location

Bay Area tide-books typically use the Golden Gate Bridge as the reference point for current. But that rolling wave means slack and peak currents happen at different times at different places throughout the bay.

Tide books also provide standard “differences” to use as corrections for other locations around the bay. (See the back of the book) – The Golden Gate Bridge is used as a reference, where currents are usually the strongest.

<< Calculating differences >>

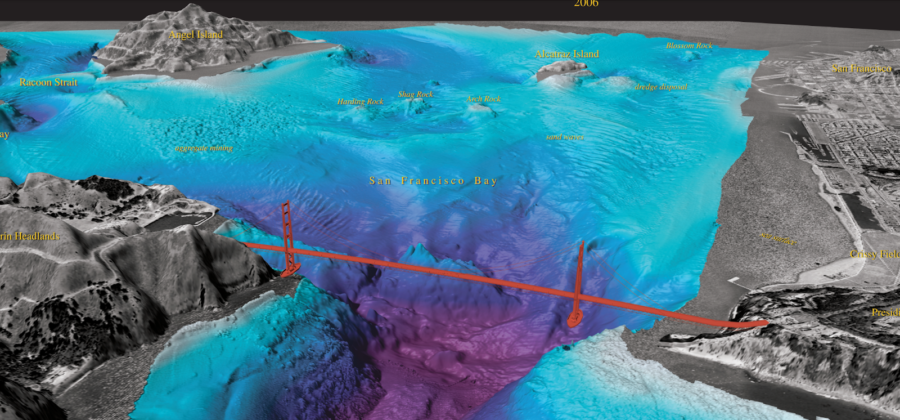

Here’s a snapshot of a typical flood. it’s just past max flood at the Golden Gate bridge with water pouring in to the bay and heading up to San Pablo bay and beyond, but you’ll notice how the water at Aquatic Park is much slower. At this point the South Bay has largely filled up, and there is much less current heading south. So while the Golden Gate is experience strong current, it might feel like slack in the cove.

Current forecasts are fairly predictable, but they are also affected by rainfall, and during wet winters the predicted currents can be significantly different from what you actually experience.

Current forecasts are fairly predictable, but in springtime, spring rains and snow melt can add to ebb current strength. More water leaves the Bay than comes in and sometimes the the predicted currents can be significantly different from what you actually experience.

Understanding Variations

Let’s dive into local current variations further. Underwater topography shapes how the water moves in and out of the bay. As the current passes obstructions, or flows from deeper areas to shallower areas, it can change in strength. In some places the current can be running at 4kts, while close by it’ll be calm or even going in the other direction.

To understand what’s happening, it helps to view the underwater topography of SF Bay. Indeed, there’s some quite interesting history behind many of these underwater geographic features. Read about that in USGS Publication, Shifting Shoals & Shattered Rocks

https://pubs.usgs.gov/sim/2006/2917/sim2917.pdf

Now, take a look at this video and watch how the bay fills and empties with current at different strengths at different parts of the cycle. See if you can spot areas of strong current and match them with whats happening underneath the surface!

Ebbing water becomes faster and more violent as you approach the constriction at the GG Bridge.

Eyeballing current.

It’s important to review the currents before you go out on the water, but there is nothing better than paying attention with your own eyes before you go out

<< Video of Eyeballing Current from the Dock >>

Planning your outing:

When going out of cove in a rowboat, kayak or paddleboard, you want to “do the hard part first.” – There’s nothing worse than having to fight to get back to the club. There’s nothing better than an easy row home after a hard workout to get somewhere.

So row out up-current (into the current) – Ride the current home to the club

An Example:

- Rowing the boat at 3.5 knots, in a 1.5 knot ebb, The right way:

- Row east making 2 knots net speed (3.5 knots rowing minus 1.5 knot of current).

- Get to Ferry Building (2 nm) in one hour.

- Return at 5 knots, getting safely to DC in 25 minutes

The wrong way:

- Row west making 5+ knots net speed

- Get to far end of Crissy Field in only 25 min.

- Turn into current (stronger close to GGB) and make less than 2 knot net speed toward home.

- Stagger back to DC in 1.5 hours or more.

Be wary of strongest ebb currents. Plan carefully.

Stay close to shore against the current and take advantage of obstacles, like piers, that block the current.

After the tides, the wind is the next biggest factor affecting the conditions of the Bay. Wind is more of a problem for rowers than swimmers, rowing into the wind can negate any current that may have been helping you

When the current and wind are in opposing directions, there will also be bigger waves and rougher water.

The wind generally blows from West to East.

- During an ebb this means that the wind will be blowing against the current creating larger surface waves.

- During a flood the wind can smooth the surface of the Bay.

Always check the weather forecast before going for a row or swim. Conditions can change rapidly while you are out and catch you unprepared.

Navigating with Current

Angle into a current when rowing across the flow:

Don’t let a current push you below (down current) from your goal. Hard rowing getting back upstream!

Sighting with two points.

I work for Caltrans. For the first 14 months I worked on bridge, fence & guardrail and landscape crews. In March I started on the boat crew and have been learning about the marine aspect of maintenance we perform on the toll bridges. Your article on Tides and Currents has given me a good perspective of tides, currents, wind and the topography which is taken into consideration when navigating the bay and inland waters. Kudos to the Dolphin Club!